Throughout American slavery and Jim Crow segregation, the Black church met the spiritual, social, economic, and physical needs of African Americans by providing resources that were systematically denied to Blacks as an oppressed group1. In contemporary society, it is estimated that almost 80% of African Americans self-identify as Christian and “more than half of all Black adults in the United States (67%) are classified as members of the historically Black Protestant church.”2,3,4 Given the historical role of the Black church in African American and Black diaspora communities, there remains a high expectation that the institution will continue to address their social, political and health concerns. However, this dynamic has been inconsistent as it relates to HIV.

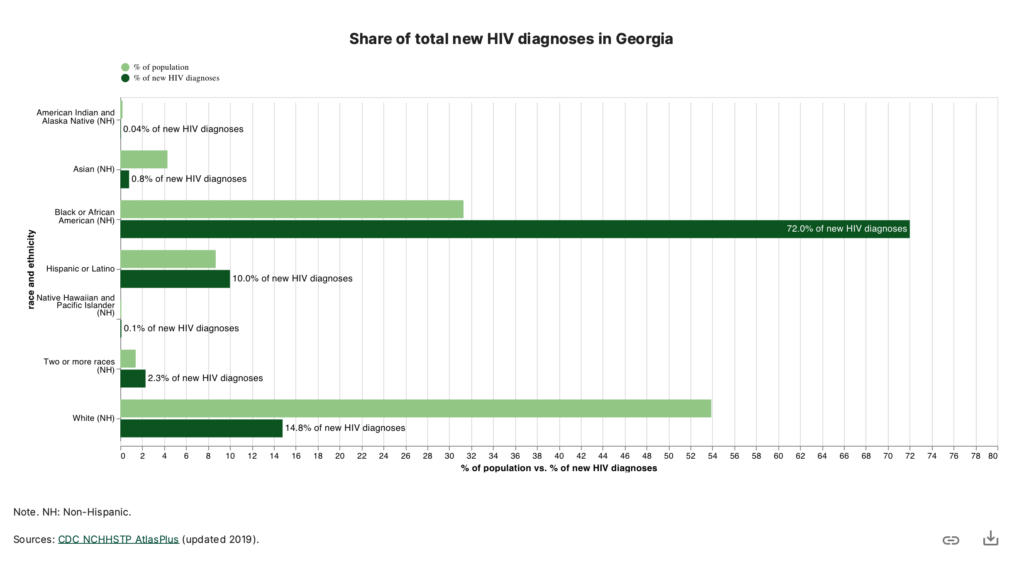

One in 16 Black men and 1 in 30 Black women are projected to be infected with HIV in their lifetime5. Despite the profound impact of HIV on the Black community, research suggests that the Black church has not devoted sufficient attention to HIV among its members6. Increasingly, Black churches have taken a more proactive outlook by ministering to the sick, the dying and the bereaved while focusing attention and sensitivity to the misunderstanding and hostility surrounding HIV and homosexuality7-9. This is particularly salient for African American gay and bisexual men (AAGBM)6 who experience high levels of homophobia, heterosexism, and stigmatization within Black churches10,11.

The Black church has a unique opportunity to contribute to the fight against HIV by leveraging its influence, resources, and community connections. However, there is strong tension between religious expectations that frown upon risk behaviors that may lead to HIV transmission, and the need to serve those who are at risk of HIV within the Black community in the United States (U.S). For many Black churches, risk behaviors that increase one’s chances of contracting HIV/ AIDS, including high-risk sex and drug use, are greatly stigmatized because such behavior is often considered taboo and contrary to biblical teaching of sin and immorality12. Indeed, the stigma of a positive HIV/AIDS diagnosis and homophobia experienced from Black churches is shown to decrease one’s coping capacity and significantly increase the experience of emotional distress13. Therefore, the support that many would expect from their faith institution becomes non-existent and even harmful.

Despite the historical and profound neglect of the Black church on supporting HIV prevention and treatment, recent data suggest that HIV prevention education, interventions, and screening are welcomed by some congregations and can be implemented quite feasibly in the Black church14. Given that the Black church and the discipline of public health often work in tandem to advance the health and wellness of Blacks in America, it is imperative that we accept that the Black church is and can be an even more formidable partner in HIV prevention6. Institutions such as Satcher Health Leadership Institute (SHLI) at Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) in Atlanta, Georgia, and Xavier University College of Pharmacy (XUCOP) of New Orleans, Louisiana should continue engaging and expanding their collaborative efforts with Black churches. Combating the current HIV crisis will take an all hands on deck approach, especially in the U.S. South where HIV disproportionately affects African American populations.

References

From physicians to policymakers, our graduates lead across sectors—creating inclusive, evidence-based solutions that improve health outcomes in underserved communities. Become a changemaker today.

Contact Us