PrEP is the acronym for pre-exposure prophylaxis. PrEP is medicine people at risk for HIV take to prevent getting HIV from sex or injection drug use. The idea behind a PrEP is to have a readily available form of HIV prevention medication. Ideally, whenever PrEP is taken as prescribed it can reduce one’s chance of getting HIV from sex by 99% or at least 74% from injection drug use1. This medication was first approved by the FDA in 2012 and it is advised that people taking PrEP are routinely screened for HIV at least once every three months2. Noteworthy is the fact that there are two approved PrEP combinations for oral administration: (a) emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, known as TDF/FTC, and (b) emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, known as TAF/FTC. While the administration of the drugs may be similar, TAF/FTC has not been FDA-approved for cisgender women3.

Today, Black people represent nearly 40% of the 1.2 million United States residents living with HIV4, yet they only represent 14% of PrEP users. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that in 2019 only 8% of Black people “who could benefit” from the drug were given prescriptions5. Comparative data shows that people of Hispanic/Latino decent represented 17% of PrEP users and White people 26% of new HIV diagnoses. The problem is that Black people, who need the drug the most are not using it. In fact, Black people and Hispanics are significantly less likely than White people to be aware of PrEP, to have discussed PrEP with a health care provider, or to have used PrEP within the past year6. Indeed, we are forced to concede that risk factors such as stigma, socioeconomic status, access to housing, access to insurance, the social, behavioral, and political determinants of health that impact many health outcomes in the Black community also affect access to and usage of PrEP. Equally alarming is the fact that these disparities can be traced along geographic lines, with the south accounting for only 30 percent of PrEP users yet representing more than half of all new HIV diagnoses in the United States3.

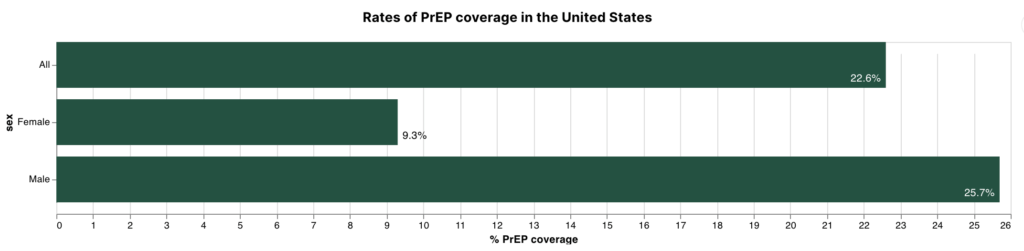

One of the primary concerns discussed by community organizers addressing the adoption of PrEP in the Black community is the observation that current PrEP commercials are often not targeted to Black women. This further underscores major gender gaps in PrEP adoption as usage is nearly three times as high among men than among women. There are also disparities based on gender identity, with only three percent of sexually active transgender people using PrEP7.

Scholars have argued that to address this level of inequity, increased knowledge of HIV status, awareness and knowledge of PrEP, access to clinicians willing and trained to provide PrEP, and support for adherence and persistence use of PrEP is required in the Black community8-10. Hence, the End the Epidemic initiative elevates efforts to support a national PrEP program that will provide greater access to care in the health care system and in nontraditional community settings. Certainly, the agreement by Gilead Sciences, Inc. to donate PrEP medication to 200,000 uninsured people at risk for HIV per year is expected to help close the health care access gap6. Noteworthy, the CDC has estimated that successful expansion of PrEP access, in combination with other interventions, can be expected to prevent as many as 1 in 5 new HIV infections each year3.

Reference

1. Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) CDC. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep.html

2. Food and Drug Administration. FDA In Brief: FDA continues to encourage ongoing education about the benefits and risks associated with PrEP, including additional steps to help reduce the risk of getting HIV. FDA. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-brief/fda-brief-fda-continues-encourage-ongoing-education-about-benefits-and-risks-associated-prep

3. Killelea A, Johnson J, Dangerfield DT, et al. Financing and Delivering Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to End the HIV Epidemic. J Law Med Ethics. 2022;50(S1):8-23. doi:10.1017/jme.2022.30

4. Varney S. HIV Preventive Care Is Supposed to Be Free in the US. So, Why Are Some Patients Still Paying? KHN. 2022. Accessed 2023, February 16. https://khn.org/news/article/prep-hiv-prevention-costs-covered-problems-insurance/

5. CDC. HIV and African American People: PrEP Coverage. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/prep-coverage.html

6. Kanny D, Jeffries IV WL, Chapin-Bardales J, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men — 23 Urban Areas, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). CDC; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6837a2.htm

7. Sevelius JM, Poteat T, Luhur WE, Reisner SL, Meyer IH. HIV Testing and PrEP Use in a National Probability Sample of Sexually Active Transgender People in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Aug 15 2020;84(5):437-442. doi:10.1097/qai.0000000000002403

8. Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav. May 2017;21(5):1256-1267. doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1

9. Bonacci RA, Smith DK, Ojikutu BO. Toward Greater Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Equity: Increasing Provision and Uptake for Black and Hispanic/Latino Individuals in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. Nov 2021;61(5 Suppl 1):S60-s72. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.027

10. García M, Harris AL. PrEP awareness and decision-making for Latino MSM in San Antonio, Texas. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184014

From physicians to policymakers, our graduates lead across sectors—creating inclusive, evidence-based solutions that improve health outcomes in underserved communities. Become a changemaker today.

Contact Us