A pivotal moment in public health occurred when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documented the first cases of AIDS in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 1981. Within that inaugural month, 26 cases were identified, with one person of Black/ African American descent. As the epidemic unfolded, a concerning trend emerged. By 1982, the CDC reported over 86 cases of AIDS among Black/ African Americans, constituting 20% of all cases that year. The gravity of the situation became even more apparent in June 1984 when a report revealed that 50% of Pediatric AIDS cases were impacting Black/African American children. A subsequent special Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 1986 delved into the disparities, highlighting that Black/African Americans accounted for 51% of all AIDS cases among women, with an overall AIDS rate 3 times higher than that of their White counterparts. This troubling trend has endured, highlighting the persistent health disparities in HIV/AIDS within the Black/ African American community.1

Contrary to popular historical narratives, the onset of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is believed to predate the widely recognized starting point in 1981. Unfortunately, this crucial side of the story often fades into the background when the history of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is recounted. The initial cases of what later became known as AIDS predominantly affected gay men of White American descent, primarily in Los Angeles and New York City. Therefore, the term “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID) was initially used to characterize the syndrome before it was eventually identified as AIDS.2

In 1969, Robert Rayford, a Black/ African American 16-year-old boy presented at a Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, with a weakened immune system and a case of chlamydia that had spread throughout his body. Although Rayford could only provide very few details, he told his doctors that his symptoms began shortly after a sexual encounter with a girl in his community. An autopsy carried out years after Rayford’s death in May 1969 revealed lesions on his skin and soft tissues from Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s Sarcoma is an aggressive cancer that later became associated with AIDS. It was not until 1987 that it was suggested that Rayford’s death may have been an HIV-related death.3

Although accounts of the earlier days of the epidemic often focused on specific populations, such as white gay men, it doesn’t diminish the fact that the epidemic has affected various communities, including heterosexual individuals, intravenous drug users, minorities of every stripe and the Black/ African American community. The history of HIV/AIDS is an intricate one that has been woven against the tapestry of a variety of factors.

1.0 What the Data Says:

1.1 HIV Incidence

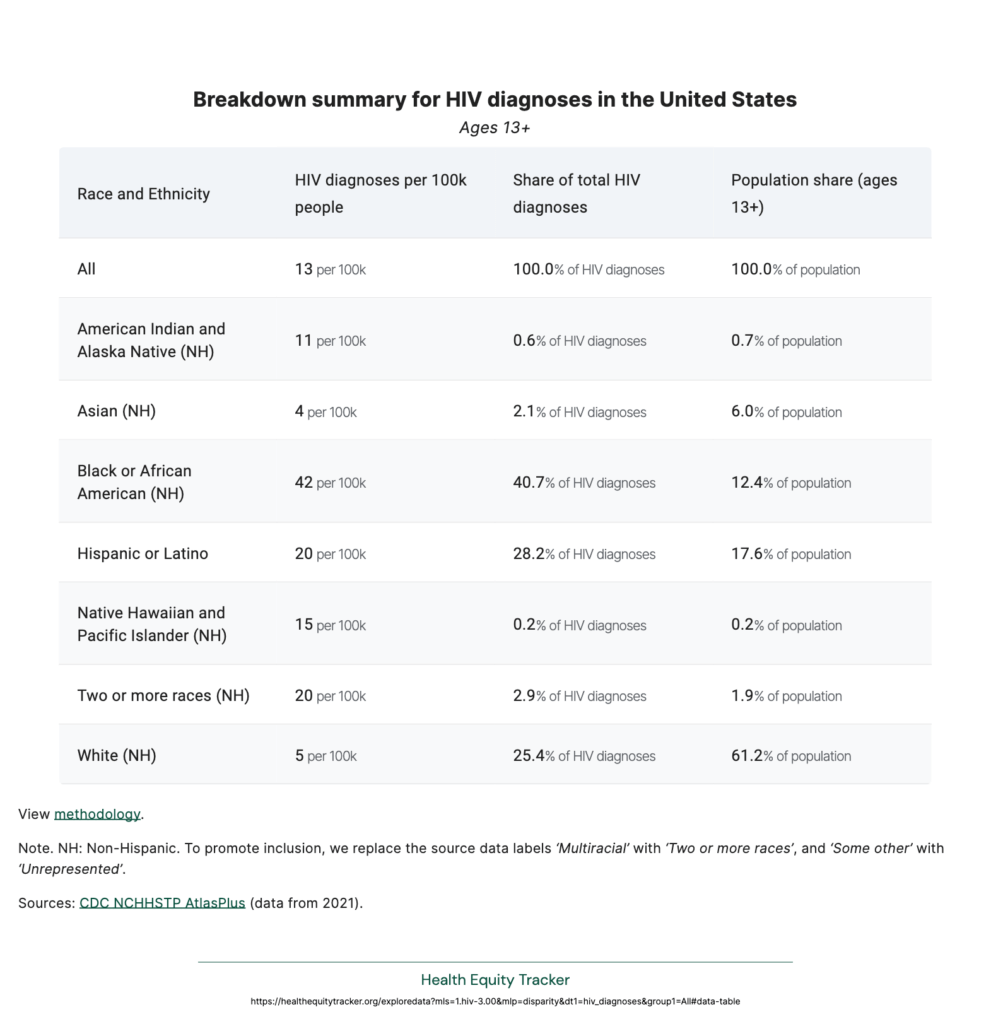

Statistics provided by the CDC in 2021 show stark disparities in new HIV infections among different racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

See Table 1 below:

5

When considering infection rates per 100,000 people, the disparities become even more distinct amongst minorities:

As of the year-end 2021, the HIV landscape among Black/ African American individuals aged ≥13 years was as follows:

These statistics further emphasize the persistent disparities in HIV prevalence, particularly among Black/ African Americans.

1.2 Deaths By AIDS

The estimated number of deaths and death rates of persons with AIDS in 2020, broken down by race and ethnicity is as follows:

These statistics provide a snapshot of the impact of AIDS on Black/African American and White American populations, highlighting that Black Americans died at a rate that was 7 times higher than their white counterparts.

1.3 Preventive Prophylaxis (PrEP Uptake)

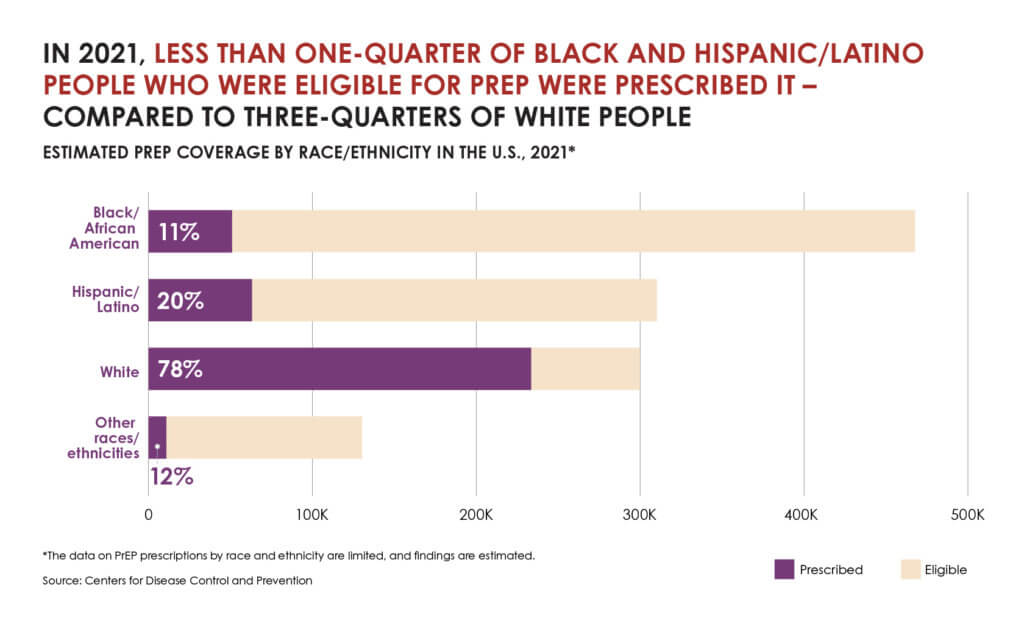

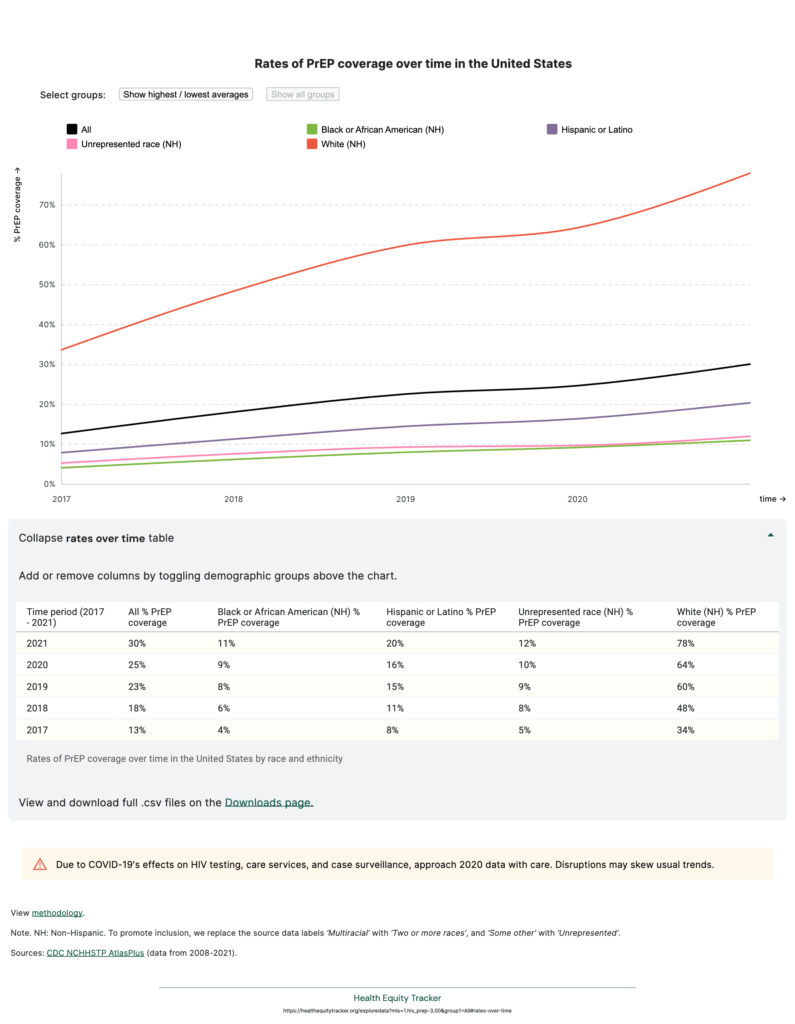

According to 2021 data from the CDC, of the 1.2 million people diagnosed with HIV, only 30% were prescribed PrEP with substantial differences by race and ethnicity.

The data further shows that less than one-quarter of Black and Hispanic/ Latino people who were eligible for PrEP were prescribed it, compared to three-quarters of White people.

The lowest rates of uptake were recorded amongst Black/ African American People, despite their overrepresentation in this group. 9

See Table 2 below:

2.0 Understanding the Drivers Behind the Disparities:

An understanding of the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on Black America remains inadequate without delving into the factors that have enabled the disparities in impact and outcomes. The journey, from the point of initial diagnosis to achieving viral suppression or, unfortunately, succumbing to AIDS, unveils a complex web of varied outcomes. Some individuals never enter the continuum, remaining undiagnosed, while others navigate it with less favorable outcomes.

In understanding and interpreting the data, it becomes evident that the numbers alone do not tell the full story, they require a nuanced analysis to inform targeted interventions and meaningful solutions.

Factors such as the social and political determinants of health play pivotal roles in shaping the trajectory of PLWHIV in our Black communities.

The Social Determinants of Health are the conditions in the environments where people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. 10 The Political Determinants of Health on the other hand create social drivers including poor environmental conditions, inadequate transportation, unsafe neighborhoods, and lack of healthy food options – that affect all other dynamics of health.11

Disparities exist for Black/ African American people across the 5 domains of the Social Determinants of Health namely, economic stability, education access, and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community contexts.

These disparities play a crucial role in understanding the association between race/ethnicity and higher risks for HIV/AIDS in addition to the overall impact on health outcomes for PLWHIV.

2.1 Economic Stability: Empirical studies have shown that HIV disproportionately affects populations facing various forms of disadvantage including lower socioeconomic status. According to the American Psychological Association, the practice of riskier health behaviors that increase the likelihood of HIV such as substance abuse and the failure to utilize condoms has been linked to a lack of economic stability.12 Unemployment rates are usually higher for PLWHIV. Therefore, with unemployment rates for Black/ African Americans being higher than the national average13, Black/ African American PLWHIV face heightened barriers to economic stability based on job insecurity and the lack of access to the socio-economic resources that guarantee quality of life and treatment adherence.

2.2 Education Access and Quality: Low educational attainment has been linked with several health disparities and negative outcomes such as self-reported poor health, shorter life expectancy, and reduced likelihood of survival when sick.14. Data from the CDC provides that approximately 13% of Black/ African American people with HIV in the U.S. still do not know their status, and few are receiving adequate HIV care and treatment that will help them achieve and maintain viral suppression, and live longer healthier lives. 15 The findings from a survey revealed that African Americans with greater educational attainment (high school diploma or greater) are more likely to report having been tested for HIV than those who have not graduated from high school.16 All of these factors combined play out for Black PLWHIV in the form of delayed or limited access to healthcare including testing, lack of reliable information about HIV treatment and prevention strategies such as PrEP, less healthy lifestyle choices, and a lack of understanding of the risks for HIV/AIDS.

2.3 Healthcare Access and Quality: Limited Access to quality healthcare for Black PLWHIV is enabled by intersecting barriers such as lack of health insurance coverage, lack of culturally competent care, the prohibitive cost of preventive measures such as PrEP, and the fear of judgment and discrimination within healthcare settings and the community.

Systemic Racism is deeply entrenched in American culture and manifests across various facets of life including healthcare. According to 83% of the participants in a focus group, Black/ African Americans are the least able to afford regular medical checkups, prescription medication, and over-the-counter medicines. 17 In the South, where Medicaid expansion is limited, uninsured Black PLWHIV face heightened challenges in accessing PrEP and other services.

2.4 Neighborhood and Built Environments: The influence of neighborhoods on HIV vulnerability is deeply rooted in historical laws and policies that have perpetuated racialized inequities. Systemic factors, such as racial residential segregation, redlining, and unfair lending practices which are relics of the Jim Crow era, gentrification, and other inequitable urban housing policies, have contributed significantly to the disparities in HIV vulnerability observed in various minority communities, especially Black communities.18 The combined effect of these systemic factors is the concentration of Black/African American communities in neighborhoods often faced with limited access to quality healthcare, reliable transportation, educational opportunities, and healthy food options, creating an environment where vulnerability to HIV is heightened. According to the CDC, in 2019, 11% of Black PLWHIV reported homelessness in the past year.19 Data also shows that People who have experienced homelessness are up to 16 times more likely to be infected with HIV. 20

2.5 Social and Community Contexts: The barriers to optimal HIV awareness, testing, and treatment within the Black/ African American community are complex and deeply intertwined with our history and culture. These barriers account for higher occurrences of HIV and the disproportionately low rates of viral suppression among Black PLWHIV. Stigmatizing beliefs, such as the misconception that HIV is predominantly a “white, gay disease,” have also hindered open discussions about HIV and enabled the reluctance to seek testing, disclose HIV status, or engage in conversations about sexual health. Also, historical instances of medical exploitation, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, have created a lasting mistrust of medical research and the healthcare system. This skepticism impedes efforts to disseminate accurate information about HIV, prevention strategies, and available treatments.

3.0 A Tale of Struggles and Triumph

While there were initial government actions to address the spread of HIV at the onset of the epidemic such as Syringe Exchange Programs to mitigate the spread of HIV and other blood-borne diseases amongst injection drug users and the establishment of the National Taskforce on the Prevention of AIDS, it was not until 1990 that a significant milestone was achieved through the enactment of the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARES) Act. The Act instituted the allocation of federal funds for the care and treatment of HIV.

The Act was named after Ryan White, a 13-year-old hemophiliac of White American descent who was diagnosed with HIV after receiving a blood transfusion in 1984.21 The CARES Act, a crucial milestone in the national response to the HIV/AIDS crisis, underscored the necessity for comprehensive resources to tackle the medical, social, and economic hurdles confronting individuals, families and communities impacted by HIV/AIDS.

The 1990s and 2000s were marked by some significant initiatives to mitigate the spread of HIV and AIDS. Whilst this list is not exhaustive, some key initiatives from this period include the following:

Recognizing the well-meaning intent behind these measures, it is crucial to note that disparities persist for Black PLWHIV. This is evident in the higher rates of HIV incidence, morbidity, mortality, and access to preventive measures such as PrEP compared to their White counterparts.

4.0 Addressing the Disparities:

Addressing disparities in HIV for Black PLWHIV necessitates a holistic approach that encompasses prevention, testing, treatment, and support services and the intersectionality of the social determinants of health. Here are a few suggested strategies to tackle the disparities and the challenges they present effectively:

4.1 Economic Stability:

4.1.1 Setting up microfinance programs through the disbursement of small loans to support entrepreneurship.

4.1.2 Providing economic incentives such as cash vouchers for treatment adherence, HIV testing, the use of condoms and other HIV prevention behaviors.

4.1.3 Providing Vocational and life skills training to encourage self-sustainability. 24

4.1.4 Educating Black PLWHIV on their legal rights in the workplace under the Americans with Disabilities Act such as protections against discrimination based on HIV status, reasonable accommodations they are entitled to, and avenues for recourse if their rights are violated.

4.2 Education Access and Quality

4.2.1 Fostering collaborations with community-based organizations, HIV/AIDS advocacy groups, faith-based institutions, and other stakeholders to leverage resources and coordinate efforts to mitigate intersecting barriers such as lack of transportation to and from school, unstable housing, and stigma amongst others.

4.2.2. Ensuring stricter adherence to anti-discrimination laws and policies in educational settings to further destigmatize HIV/AIDS.

4.2.3 Implementing easily accessible financial aid programs tailored specifically for Black PLWHIV to empower them to achieve their highest potential, irrespective of their HIV status.

4.3 Healthcare Access and Quality:

4..3.1 Expanding Medicaid in all 12 states that have yet to fully adopt it as this will be crucial for providing health insurance coverage to uninsured or underinsured Black PLWHIV, leading to increased access to HIV treatment and prevention and ultimately improved health outcomes.

4.3.2 Encouraging the development of trusting and supportive relationships between patients and healthcare providers, which are essential for effective shared decision-making regarding HIV prevention strategies like PrEP.

4.3.3 Creating a model that bundles healthcare with other social services that acknowledge and respond to the unique needs and experiences of Black PLWHIV to alleviate the barriers to healthcare access such as the complexities of navigating the healthcare system.

4.3.4 Training healthcare providers and social workers to deliver culturally competent, nonjudgmental, and patient-centered care, in addition to providing tailored educational resources in multiple languages that are reflective of the communities they serve.

4.4 Neighborhood and Built Environments:

4.4.1 Forging partnerships with local housing authorities, community-based organizations, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders to increase alignment with existing local initiatives aimed at ending the HIV epidemic in a way that integrates affordable and quality housing as a structural intervention within broader HIV prevention and care models.

4.4.2 Implementing proper mechanisms for bundling services, information sharing, and referral pathways, to ensure seamless delivery of housing and other supportive services for Black PLWHIV.

4.4.3 Establishing down payment assistance programs specifically designed to help Black PLWHIV overcome the financial barriers of upfront costs associated with purchasing a home, increasing access to affordable credit, and property tax reliefs for low-income Black PLWHIV homeowners.

4.5 Social and Community Contexts:

4.5.1 Embracing an approach to law and policymaking as well as advocacy that includes amplifying the voices and perspectives of Black PLWHIV through their maximum involvement.

4.5.2 Engaging in Community-led initiatives, including peer support groups, outreach programs, and social media campaigns to destigmatize HIV, raise awareness, encourage open discussions, and promote the uptake of PrEP, HIV Testing, and other preventive measures among Black PLWHIV.

4.5.3 Increasing funding for Community Based Organizations through more easily accessible models to enable them build resilience within their communities, ensure optimal service utilization by at-risk populations and to support the national vision of HIV surveillance and prevention effectively and efficiently.

While our recommendations are constrained by scope, we are optimistic that the suggestions outlined here will play an essential role in implementing targeted interventions and tailored solutions to improve outcomes for Black People Living With HIV.

References

From physicians to policymakers, our graduates lead across sectors—creating inclusive, evidence-based solutions that improve health outcomes in underserved communities. Become a changemaker today.

Contact Us