Historically, minoritized communities have endured discrimination based on race, ethnicity, and sexual and gender identity (LGBTQIA+). Such discrimination has been closely associated with negative mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety disorders, suicidality, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Untangling the complex relationship between discrimination and health reveals a multifaceted impact on well-being. Those who report facing discrimination in their daily lives are more prone to experiencing adverse effects such as heightened worry, stress, feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression. Discrimination serves as both a primary stressor and an underlying factor affecting mental health.

Accessing mental health care is often challenging for individuals from minoritized communities. Barriers such as inadequate healthcare coverage, expensive copays, out-of-pocket expenses, limited availability of providers in certain geographic areas, and time constraints hinder their ability to seek care. These obstacles perpetuate inequities in mental health treatment and exacerbate the impact of discrimination on well-being.

Discrimination among Minoritized Populations

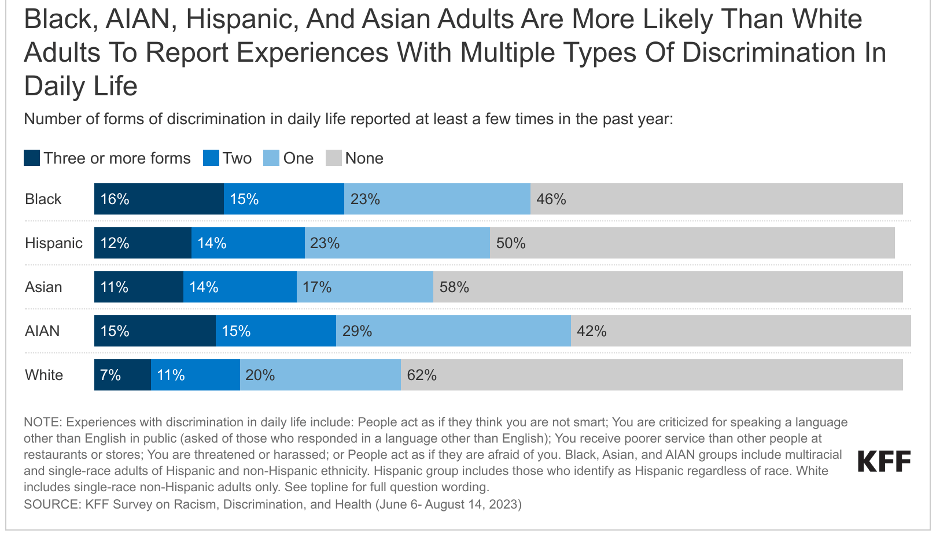

According to a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation:

At least half of Indigenous, Black, and Hispanic adults and about four in ten Asian adults say they have experienced at least one type of discrimination in daily life at least a few times in the past year, and they are more likely to say these experiences were due to their race or ethnicity compared to their White counterparts.1

For example, those who experienced discrimination in their everyday lives are at least twice as likely as those who report rarely or never experiencing discrimination to say that in the past 30 days worry or stress has led to sleep problems (65% vs. 35%); poor appetite or overeating (52% vs. 20%) frequent headaches or stomachaches (41% vs. 15%); difficulty controlling their temper (34% vs. 11%); worsening of chronic conditions (19% vs. 9%); or an increase in their alcohol or drug use (19% vs. 6%).1 Similarly, those who have experienced discrimination are more likely than those who haven’t had these experiences to say they always or often felt anxious, lonely, or depressed in the past year. 1 (Figures 1-2)

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

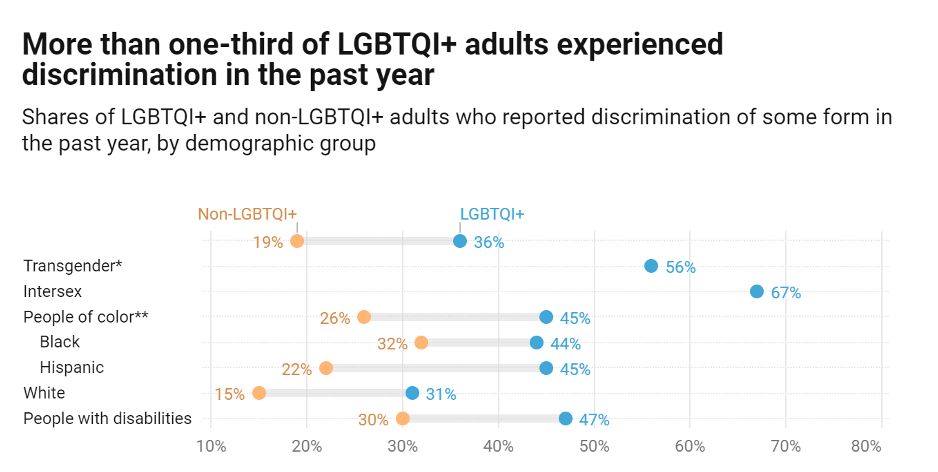

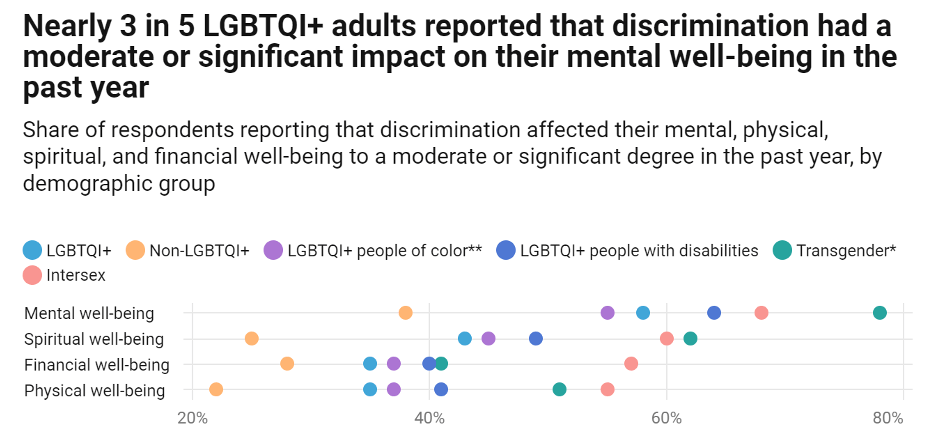

Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) or those from the LGBTQIA+ community face both structural and interpersonal discrimination, which significantly impacts their health.2 However, the current landscape of nondiscrimination laws across states and gaps in federal civil rights laws leave many SGM individuals vulnerable to discrimination.2 There has been a concerning surge in state-level attacks explicitly aimed at curtailing the rights of SGM individuals, particularly SGM youth and transgender individuals.2 In 2022 alone, over 300 bills were introduced by state lawmakers targeting the rights of SGM individuals.2 These discriminatory policies are closely intertwined with and fuel the increase in extremist anti-SGM, especially anti-transgender, rhetoric, dissemination of misinformation, and instances of violence.2

SGM individuals continue to experience significantly higher rates of discrimination than non-SGM individuals, a trend that holds true in virtually every setting including health care, employment, housing, and public spaces. Such discrimination has substantial adverse effects on economic, physical, and mental well-being, and many SGM individuals alter their behavior to avoid experiencing discrimination.3-4 Due to the oppressive influences of racism, transphobia, and ableism, transgender individuals, SGM people of color, and SGM individuals with disabilities generally report experiencing discrimination at rates higher than those of other SGM individuals and of non-SGM individuals.3-4

A 2022, Center for American Progress survey identified that:3 (Figures 3-4)

Nearly 4 in 5 SGM adults reported they took at least one action to avoid experiencing discrimination based on their sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status, including avoiding medical offices.

More than 1 in 3 SGM adults reported postponing or avoiding medical care in the past year due to cost issues, including more than half of transgender or nonbinary respondents.

More than half of SGM adults reported that “recent debates about state laws restricting the rights of SGM people” moderately or significantly affected their mental health or made them feel less safe, including more than 8 in 10 transgender or nonbinary individuals.

Approximately 1 in 3 SGM adults reported encountering at least one kind of negative experience or form of mistreatment when interacting with a mental health professional in the past year.

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

The Impacts of the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) on the Health of Minoritized Communities

The social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, play, pray, and age, as well as the systems put in place to deal with illness. SDoH affect a wide range of health, functioning, quality-of-life outcomes, and risks.5 Minoritized populations often live and work in places that do not provide equal access to healthy food, safe housing, and regular medical care. These factors can drive as much as 80 percent of health outcomes. Discrimination exacerbates health inequities in minoritized communities by impacting physical health through physiological stress and indirectly through the inequitable opportunities for achieving good health in their environment.5

Black people face an array of underlying structural inequities in social and economic factors that are major drivers of health. One of the most significant factors is ongoing residential segregation. A large share of the Black population live in urban areas that have less access to resources that support health and that pose more exposure to health risks.5

Black people are more likely to live in areas that have more limited educational and employment opportunities, more limited access to healthy food options, less access to green spaces, and more limited transportation options, which in turn make it more difficult to access health coverage and care and pursue healthy activities.6 Moreover, many of these areas pose increased environmental and climate-related health risks, including increased exposure to extreme heat, lead, pollution, and toxic or hazardous materials.6

Several risk factors for disease and social determinants of health have unique histories in the Indigenous population, including historical trauma, adverse childhood experiences, poverty, federal food programs, and food deserts. Indigenous people residing in poor communities often lack access to public transportation, quality education, infrastructure (i.e. broadband), housing, affordable and nutritious food, jobs, and health care.7

Hispanic health is often shaped by SDoH factors. Language and cultural barriers, as well as higher levels of poverty, lack of access to preventive care, and the lack of health insurance are among the social and economic factors contributing to inequitable health outcomes for Hispanic Americans. As of 2021, the uninsured rate among Hispanics under age 65 was 19%, according to KFF, formerly. That was higher than the share among Black (11%), White (7%), and Asian Americans (6%). Hispanic people have less access to quality medical care where they live.8

Sexual and gender minorities may have higher rates of housing insecurity, housing instability, food insecurity, and financial insecurity as adults due to adverse childhood experiences or policies that exacerbate economic inequities.3

Impediments to Equitable Access to Quality Healthcare among Minoritized Communities

Access to quality healthcare is a major impediment to the health of minoritized communities. This is due to a range of interconnected factors. These factors may include systemic barriers such as economic inequities and built-environment limitations such as access to transportation.9 Cultural and language barriers can impede effective communication and understanding between healthcare providers and historically underserved communities, further exacerbating the issue.9 Implicit biases and discriminatory practices within the healthcare system can contribute to unequal treatment and access to care based on race, ethnicity, sexual or gender minority status.6,9 Economic inequities experienced by minoritized communities such as unemployment and lack of insurance continues to drive limited access to quality healthcare. Many people from racial and ethnic minority groups have difficulty getting mental health care.2 This can be due to many different reasons, such as cost or not having adequate health insurance coverage.2,3,4 It is also challenging for minoritized populations to find racially or behaviorally concordant physicians and healthcare providers. Stigma or negative ideas about mental health care may also prevent people from seeking services.

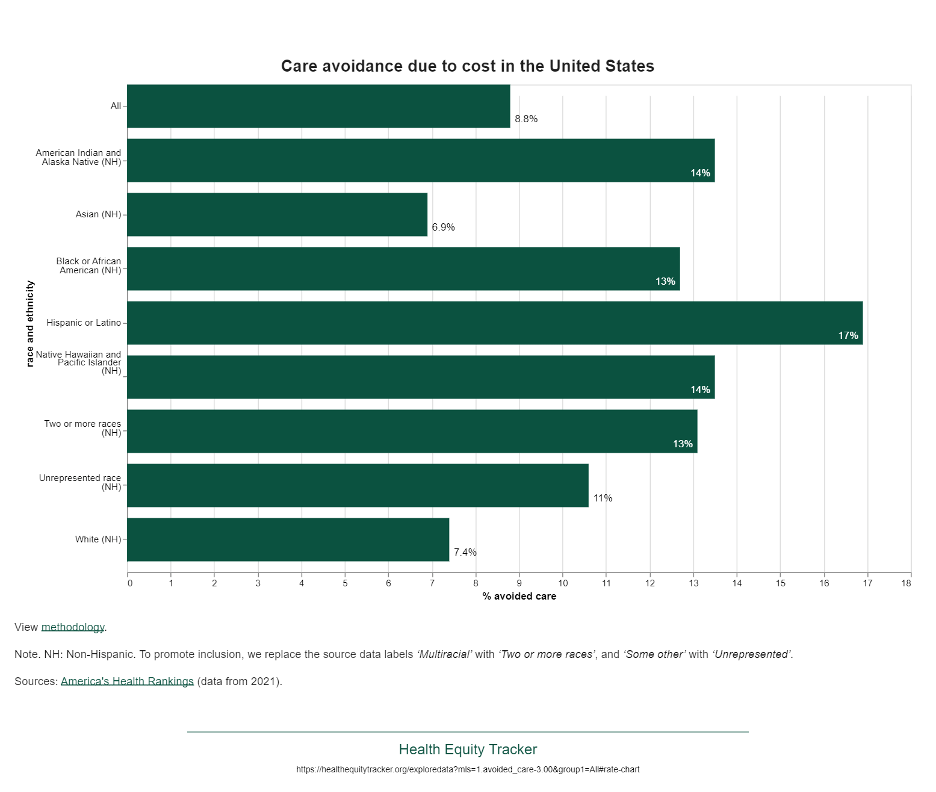

Care Avoidance Due to Cost

Discrimination continues to leave minoritized communities with severe mental health disorders and concerns. The percentage of people who forgo mental health care because of its cost has continued to increase. The odds of having health insurance were 40 percent lower for people with serious psychological distress (SPD) than those who did not have SPD.11

Rates of mental health care for people with severe mental illness are lowest for the uninsured and highest for those with public insurance, while those with private insurance fall between the other groups. Even among the insured, costs may be a barrier to getting needed mental health care.12 Only 56% of psychiatrists accept commercial insurance, in contrast to 90% of other non-mental health physicians. Insurers typically reimburse licensed mental health professionals at lower rates compared to physicians with similar qualifications and experience. Consequently, individuals seeking mental health care are over five times more likely to turn to out-of-network mental health professionals than to medical or surgical services.13

Cost sharing may disproportionately affect people with mental health disorders, who have lower family incomes and are more likely to be living in poverty than those without mental health disorders. Based on a Kaiser Foundation study on how cost affected access to healthcare in 2022, more than 1 in 4 adults (28%) reported delaying or going without either medical care, prescription drugs, mental health care, or dental care due to cost.9 More specifically, the number of Americans reporting that they forgo mental health care due to cost has steadily increased. At least one in five adults across minoritized populations say they or a family member living with them had a problem paying for health care in the past 12 months.9 Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to report problems affording health care in the past year (27% vs. 23%), reflecting that they have a higher rate of being uninsured.9

Left untreated, mental health disorders affect the well-being of children, adults, families, and communities—both because of the emotional costs as well as the economic ramifications. Paying for health care is a common challenge across minoritized populations.11

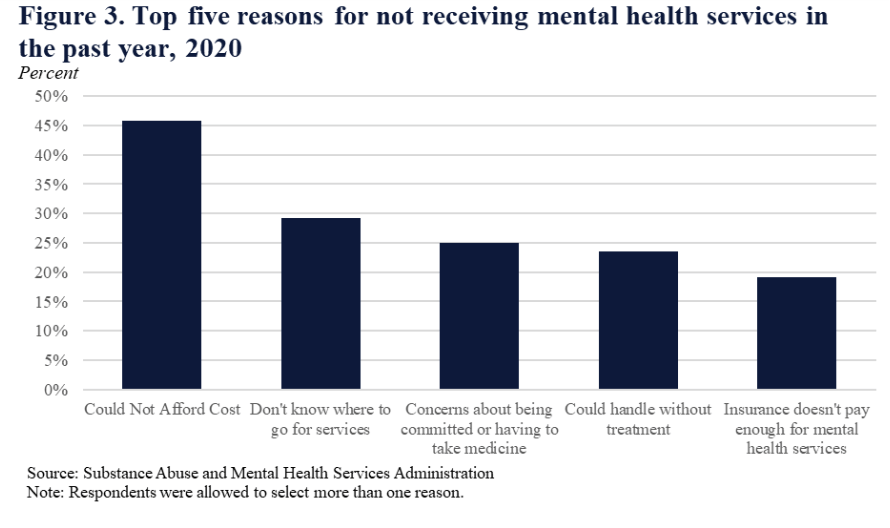

When analyzing care avoidance due to cost based on Satcher Health Leadership Institute’s Health Equity Tracker, we learn that minoritized populations, specifically Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous populations report care avoidance due to cost at higher percentages than their white counterparts (Figure 5). According to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, in 2020, the top reason that Americans did not seek mental health services was due to unaffordability and cost (Figure 6). Americans reported having to choose between getting mental health treatment and paying for daily necessities.

Figure 5:

https://healthequitytracker.org/exploredata?mls=1.avoided_care-3.00&group1=All#rate-chart

Figure 6:

Expanding health insurance coverage plays a vital role in overcoming financial barriers to accessing necessary treatment, especially in mental health care. Research increasingly demonstrates that having health insurance directly correlates with higher utilization of effective mental health services and helps alleviate stressors that can negatively impact mental well-being. However, political decisions, such as the refusal of some states to expand Medicaid, exacerbate cost-related barriers to mental health services.12

Studies have revealed that Medicaid expansions lead to greater utilization of mental health services and alleviate financial strain for individuals. By reducing the likelihood of borrowing money or skipping other bill payments due to medical expenses by more than half, Medicaid expansion essentially eliminates catastrophic out-of-pocket medical costs. This reduction in financial burden likely contributes to improved mental health outcomes.12

Policymakers could enhance the affordability and accessibility of behavioral health care, including mental health services, through various means. These include enforcing network adequacy and parity provisions, reducing patient costs, and incentivizing provider participation in insurer networks.13 Existing frameworks aimed at improving affordability and access provide a foundation upon which policymakers can build. Strengthening parity frameworks, leveraging the Affordable Care Act’s provisions for no-cost sharing in preventive behavioral health services, and establishing enforcement mechanisms independent of consumer complaints are critical steps for policymakers to consider.13

By Tonyka McKinney

Postdoctoral Fellow, Political Determinants of Health

Satcher Health Leadership Institute

Morehouse School of Medicine

References

From physicians to policymakers, our graduates lead across sectors—creating inclusive, evidence-based solutions that improve health outcomes in underserved communities. Become a changemaker today.

Contact Us